Inquiry

Initial inquiry proposal - 02/10/24

Initially, I was spurred into my inquiry question by one of my chemistry-specific classes discussing First People's Principles of Learning and how we teach science. The idea presented by research was that low educational attainment in science by First Nations students is caused by a sort of cultural incompatibility (Thiessen, 2001).

I was taken aback by this statement. Not only do I not understand how this could be concluded but with my current knowledge of both topics I can't agree with this statement. This may change as I educate myself further on the topic.

Therefore, my proposed question is "What are the differences in First Nations student's culture and schooling that prevents them from excelling in western science?"

When generating my inquiry question, there was four questions that needed to be answered:

1)What is your question and how did it arise for you?

The idea presented by research that low educational attainment in science by First Nations students is caused by a sort of cultural incompatibility (Thiessen, 2001).

2)Why is your question significant (to you and/or to others)?

Initially, I was taken by how discriminatory this statement felt. Often sciences can and are gatekeepers for many individuals. I worry that this broad statement can detrimentally affect First Nation student's futures and learning. Furthermore, the effect on the wider BC school system.

3)What resources will you draw on to explore your question? (e.g., journal, readings, curriculum/policy documents)

I foresee having to draw on multiple forms of documentation, journals, and readings, as well as reaching out to rural school districts and First Nation groups to gain deeper knowledge.

4)What do you expect to find out?

I don't know what I will find out, but I'm excited to explore and educate myself more on the topics.

See you back for an update soon.........

Inquiry Research Paper - 02/12/25

First Nation Science in a Western Education System: The Supposed Incompatibility between Science and First People’s Way of Learning.

For generations, the First Peoples of Canada endured profound hardships due to the residential school system imposed on them. Designed to assimilate rather than educate, this system systematically erased Indigenous languages, cultures, identities, and traditional knowledge. Due to sheer ignorance, the First Peoples’ rich education system, one that was deeply rooted in the land and their connection to it, was overwritten and replaced. While thankfully the residential schools have all been closed, Indigenous students are still suffering in the Canadian school systems for different reasons. In a 2006 Canadian census, it was found that only “40% of Inuit, 50% of First Nations, and 75% of Métis youth aged 20–24 graduated from high school” compared to 89% attainment by non- indigenous learners (Council of Ministers of Education, 2012). Science education has specifically seen some of the highest dropout and low achievement rates from Indigenous students (Kim, 2016). The subject has been reported as having a sort of cultural incompatibility with First Nations ways of learning causing a roadblock for Indigenous students to get into STEM-based professions (Thiessen, 2001). However, why is this the case? The First peoples used science long before colonization by the English and French. To explore this issue, an analysis of Indigenous science, western science, and the incompatibilities between them will be used to develop suggestions to help.

The First Peoples of Canada have used science from time immemorial to survive in often unforgiving environments. When British and French colonizers came from Europe many saw the different tribes they encountered as uncultured savages. However, this couldn't be farther from the truth. Looking at Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, it can be seen that without the development of science and engineering the First Peoples would not have been able to attain the depth of culture, respect for nature, and knowledge we see today. The novel Braiding Sweet Grass by Robin Wall Kimmerer a member of the Potawatomi nation beautifully explains what Indigenous science truly means. She shares that Indigenous science is seeing the world as one connected organism that is "bound to every other [species] in a reciprocal relationship" and listening to those "teachers among the other species for guidance" as "humans have the least experience with how to live and [have the] most to learn" (Robin Wall Kimmerer, 2013). The key to science is observation, without it no patterns, behaviours, causations, or relationships between organisms or materials would be able to be discovered. The First Peoples carried and preserved these intricate relationships over thousands of years through oral stories and teaching. If they never prized science these knowledge bases would have been long lost to time. Another key aspect of science is experimentation. The Ehattesaht and Quatsino people of Vancouver Island would have used experimentation to collect a deep sea creature called the dentalium. A type of mollusc their shells were used for centuries as a type of currency all along the west coast of Alaska down to Mexico. However, these creatures lived far too below the surface to be dived for. Historical reports a "device with a very long handle and a bottom end resembling a “great, stiff broom” was used to pluck live dentalia from the seabed" and would have been worked by a single person in a canoe (Snively & Wanosts'a7 Lorna Williams, 2016). This contraption would have needed not only a deep understanding of the chemical and physical properties of the material used to build it but also fine technical skills to harvest only what was needed and not disturb the sea floor. Not to mention countless experiments, prototypes, and iterations to create a successful working model. Overall, there are countless examples showing the complex scientific knowledge and engineering that has always existed within the different First People's cultures.

In Western culture, there is a large focus on the individual rather than the whole and this can be seen evidently in how we developed science. In Western science, the focus is on isolating different variables from small systems and testing them to see what they do and how they can affect the system. However, unlike Indigenous science which focuses on the whole and moves down, Western science often forgets the whole to focus on the small. There have been countless examples of chemicals or processes being developed and used extensively without proper research on their larger and often detrimental effect on people or the environment. One famous example would be DDT or dichloro-diphenyl- trichloroethane which was developed during the 1940s as an insecticide and is still used today in some African countries. However, it has a detrimental effect on the environment as it has a long half-life, and has been found to cause birth defects, as well as causing cancerous tumors. Western culture as reflected in its science also is usually only interested in dominating others and exploiting the world around us to stay on top. While it has led to countless discoveries rather quickly it has also decimated our planet and the creatures that live on it.

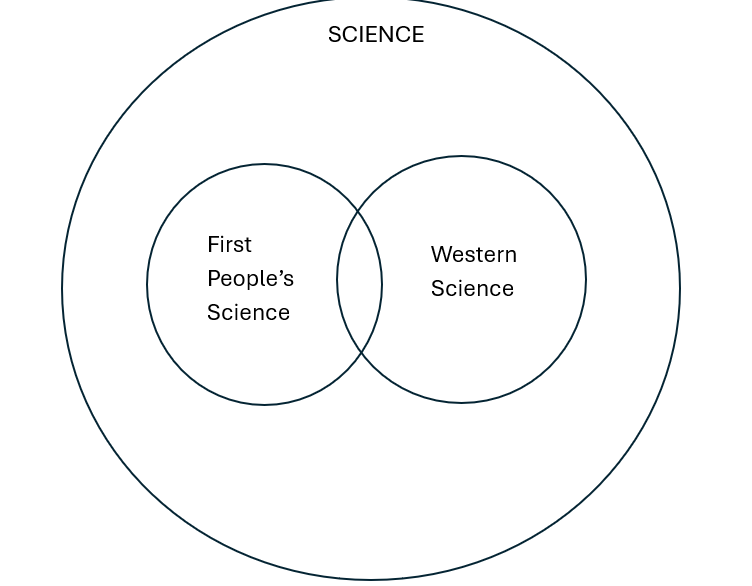

The science curriculum taught in Canadian schools if not all schools around the world is focused on this type of Western science. Students are focused more on writing reports than seeing the connection between them and the animals, understanding that trees and mushrooms do hold memories and talk to one another, and learning empathy for other living things. This is why Indigeonus ways of knowing are incompatible not with science itself but with parts of Western science. This difference is key to mention as often people don't understand what science is. Science is the process of using inductive and deductive thinking to study the processes and rules that govern the world around us. Within this definition, we can place “subcultures” of both Western science which focuses more on the micro scale, with written records, and isolated variables and Indigenous science which focuses on the macro scale, with oral records, and connected variables. When we look at science in this way, a path forward for integrating the two into the Canadian science curriculum becomes less daunting. While the current BC curriculum has been updated with a series of First Peoples Principles of Learning for teachers to follow there is still a lack of understanding, training and, resources provided to teachers. If anything it feels like the tokenization of First Nations knowledge. How do we balance the two subcultures of science and encourage the crossing between the two by all students? A study done on African scientists moving between a Western scientific laboratory and their tribal village found that while there were evident contradictions between the types of thinking and beliefs occurring they were able to traverse the difference effortlessly (Aikenhead, 1997). However, with adolescents, this traversing between the worlds of their families, peer groups, schools, and classrooms was found to happen not as smoothly often requiring assistance from adults, most notably at school (Aikenhead, 1997). This difficulty in traversing between two ways of knowing and lack of help could be a large reason why Indigenous students find science classrooms daunting. Therefore, the development of a curriculum and instructional materials that not only help students make the transitions between the different subcultures of science, support students' personal and cultural ways of knowing, and teach Western science material in the context of societal roles is vital to supporting Indigenous students in the classroom (Aikenhead, 1997).

The integration of Indigenous and Western sciences within the Canadian education system is essential for fostering reconciliation, deeper scientific understanding, and creating a brighter future for all. Indigenous science is a subculture of science, rooted in a holistic relationship with the natural world, offering profound insights into astronomy, biology, medicine, sustainability, and interconnectedness. Differently, Western science another subculture of science, is very analytical, isolated, and often overlooks the broader implications of its discoveries. Canadian classrooms which teach Western Science force Indigenous students to assimilate, disregarding their worldview and traditional knowledge base, creating barriers for Indigenous students and limiting their engagement with STEM fields. However, helping students journey between the two subcultures, creating culturally responsive curricula, and teaching Western science in the context of societal roles will help get Indigenous back in science classrooms.

References

Aikenhead, G. S. (1997). Toward a First Nations cross-cultural science and technology curriculum. Science Education, 81(2), 217–238.

https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-237x(199704)81:2%3C217::aid-sce6%3E3.0.c o;2-i

Council of Ministers of Education. (2012). Literature review on factors affecting the transition of Aboriginal youth from school to work. CMEC, Canada. Retrieved November 30, 2024 from

https://www.cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/298/Literatur e-Review-on-Factors_EN.pdf

Kim, M. (2016). Indigenous knowledge in Canadian science curricula: cases from Western Canada. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 12(3), 605–613.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-016-9759-z

Robin Wall Kimmerer. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions.

Snively, G., & Wanosts'a7 Lorna Williams. (2016). Knowing Home: Braiding Indigenous science with Western science. University Of Victoria.

Thiessen, V. (2001). Policy research issues for Canadian youth: School-work

transitions (R-01-4-1E). Applied Research Branch Strategic Policy Human Resources Development Canada. Retrieved January 11, 2006, from http://www.arts.yorku.ca/soci/anisef/courses/4630/docs/pdf/thiessentransitions. pdf

Reflection

Overall, the base of my inquiry question did not change much over the couple of months. However, as I researched, I noticed that if I only included research around BC’s First Nations my already limited sources would become even less. So, I changed from “First Nation Science in BC’s Western Education System” to “First Nation Science in a Western Education System: The Supposed Incompatibility between Science and First People’s Way of Learning” with a focus on BC First Nation groups. I first wanted to figure out and define what is the science of the First Peoples. Overall, I found that the idea that both Western and Indigenous science is within the greater world of science felt right. Both have their own approaches to science while also sharing some.

I ended up using sources from across the world and found overall that the main issue discouraging indigenous students from being successful in the science class is the teacher is 1) not knowledgeable about their areas First Nations and culture, 2) only focusing on Western science perspectives, 3) not having help for First Nation students jumping between two knowledge systems. I want to state again that there is very limit information and statistics regarding these marginalised groups and are overly generalized, lumping all First Nation students together. This means that there is no end to this inquiry question, and it would be hard to come to conclusions during my long practicum. Therefore, I will try to further educate myself on local bands and/or groups at NWS, furthermore, ask the indigenous teacher at NWS to build material and my knowledge base to educate from. My PLC question that I used “The Explanation Game” would be fantastic to intergrade scaffolding for all students but also First Nation students in my classroom as it allows them to not only explain their worldview but also explore it. Similarly, the inquiry aspect of IB I think would be very beneficial for First Nation students to explore their interest, not simply listing to Western science knowledge shoved down their throats. My main goal is to make sure all students thrive and feel comfortable in my classroom, and I hope that my further research into this topic will help First Nation students stay in science classrooms.